Blog moved

August 28, 2012 Leave a comment

I’ve incorporated my blog into my new business website.

Find it at Editorial Partners/Blog.

Exploring Emerging Technologies in Learning

August 28, 2012 Leave a comment

I’ve incorporated my blog into my new business website.

Find it at Editorial Partners/Blog.

April 20, 2012 2 Comments

Third-party hosting services (like WordPress!), as our readings point out, have several disadvantages, including their potential instability (i.e., they can disappear at any time, taking your content with them) as well as the lack of control you have over what else happens in that space (our reading’s example was YouTube advertising; I would also add commenting, because this is the reason many schools in my area block access to YouTube).

For my final project, I chose to set up a wiki because I wanted to learn how to use a new tool. But the wiki-hosting sites do not allow a lot of customization; in my case, I want to be able to control formatting, colors, and so on. In addition, free wiki-hosting sites also have some potential for putting ads on your wiki. (For instance, one OER I visited in my quest had advertisements from the Koch brothers—right-wing owners of the second largest private company in the United States—ads that were a complete contradiction to the stated purpose of the site itself.

So instead of choosing a third-party site, I decided to self-publish my wiki using a new site for my business. I am moving my files, etc., from Yahoo Small Business hosting (which charges $35 a month to host my website) to Bluehost.com, which charges only $6 a month. When I first started my freelance business, I knew nothing about Web publishing and those were also the days of raw HTML. Yahoo offered a service to help build the site, and so I chose that option. Fast forward to now, in which not only have I learned a lot about Web publishing but also I have access to mountains of free tools to help me build a site. Bluehost is wonderful, too, because it has scripts that will set up a WordPress or wiki engine for you. So my hosted account Editorial Partners LLC is the host of my Professional Writing wiki, the final project for my course and an ongoing project for me.

For only $6 a month, an amount many people spend daily on a latte or chai tea from Starbucks, I have a space on the Web that is entirely mine: I control what’s there (and what’s not), there are no unwanted advertisements, very few schools have blocked the site from their students (none, actually), and it will never disappear unless I make it. I can change colors, change my whole theme, create subdirectories for different projects or clients, and so on. In addition, I researched different types of wikis and chose Dokuwiki as my engine because it creates text files rather than database entries, which means they are accessible on any device, easily printed, and require relatively low bandwidth and memory. And because they are text files, they play well with audio devices for people with sight disabilities and can be saved as a document that can easily be modified (e.g., scaling up the font size).

The only “down side” that I see (aside from the programming bits I need to learn—and for me, learning new tools never has a down side) is that these resources are less easily found on the Web. For instance, if I google “professional writing resources,” my little wiki does not appear in the search results. Perhaps that is something to add to the course resources, in the area of publishing: the basics of metadata, how search engines can find you, how you could submit to OER respositories, etc.

April 18, 2012 Leave a comment

As I have been creating and compiling my final project for Open Educational Resources, the question of copyright has come up several times before we have actually gotten to the subject in our course readings.

I’m not unfamiliar with questions of copyright because part of my work is in educational publishing. In that professional space, permissions is a unique function for textbook publishers who wish to use others’ material in their books or to republish, for example, a storybook for children put out by a trade publisher. For instance, currently I’m wrapping up a book for K–8 teachers on writing research, a resource guide that reprints article excerpts from a number of research studies on children’s writing development, teaching strategies shown to work, writing and technology, and so on. Each has to be permissioned from its originating source, whether an academic journal or a book. Luckily in my role as compiler and editor, I hand off the permissioning function to an outside freelancer who specializes in this area.

I say “luckily” because I find the whole thing sorta boring to me, for the same reason I didn’t follow the other English majors from Washington University to law school after we graduated.

But thinking about copyright, fair use, and all that in the context of OERs is more complicated and thus more interesting. When you publish an OER, the “O” says it all: you have opened up your thoughts and skills to a very wide audience that will do all sorts of things with them you could not have imagined. Unlike a traditional academic publishing model, where there is a sort of weird secrecy about what you’re working on until you actually publish something or present it at a conference, publishing in the “O” space is immediately public. And no matter what, you have absolutely no control over what people do with your content. Put all the licensing options you want on it, it is still electronic and on the Web and by definition is thus easily replicable. Contrasted with a book, which you could only remix and reuse if you retyped the whole thing or photocopied/scanned it, bits and bytes are really easy to reproduce. With CC-BY and other restrictions, unless someone gets caught reusing materials, the originator is left pretty much relying on the goodwill of others, hoping that they honor her wishes as to how “open” the material is. On the other hand, outright stealing is easy to find if you look for it.

A few years ago, I had the experience of catching a plagiarist who was trying to pass off part of a short reader as her own work. The reader was one of the small, paper books typically accompanying large published reading programs for textbook publishers of early grade materials. As I was reading the manuscript, I had that funny feeling seasoned writing teachers get when something about a student’s work just doesn’t feel quite right: you are reading along, and you realize that the voice you had gotten used to somehow…shifted as suddenly the kid writing in simple sentences becomes almost wordy and complex. The little book was about the solar system, and so I typed directly into Google (with surrounding quotation marks) a couple of the sentences that struck me as different from the rest of the book. And lo and behold, I arrived at the PBS website to find several paragraphs of the “original” manuscript.

(As an aside…stealing words from PBS? Like stealing wine from a cathedral: sinful.)

Likewise, if someone used your work on the Web, it maybe pretty easy to find if you have some suspicion it’s out there. But what if they used your work in another context? It would be impossible to attend every lecture, watch every YouTube video, or visit every classroom that might be using your materials. It seems to me that if you publish Internet materials, you have already entered the O space, whether you define your materials as available for remix or reuse or not. It’s a tricky space to be in. In my final OER project I mostly link to other materials, many of which are copyrighted, rather than try to embed them or rework them in some way. To do this is the easy way to acknowledge the creation of others as well as to demonstrate (potentially) how to use them in a context that I am creating, much like academic papers cite sources of other ideas and conclusions.

March 12, 2012 3 Comments

Right now, I’m not teaching courses, but my final project for Open Educational Resources at the University of Manitoba will also be something that I will use for a series of training workshops I’ve been asked to set up. Thus I’ve already been thinking about integrating my aggregation of OERs within the context of 2-hour workshops over a series of several weeks, but our readings this week help me organize my thoughts a bit:

Our text describes eight steps to OER integrating OER in teaching and learning.

- Assess the validity and reliability of the OER.

- Determine placement within the curriculum, if not already done. Note that some OER integration may be abandoned at this point if the OER relates poorly to the rest of the curriculum.

- Check for license compatibility. (See License Incompatibility in Licensing for more details).

- Eliminate extraneous content within the OER (assuming the license permits derivatives).

- Identify areas of localization (see Adapt OER).

- Remix with other educational materials, if applicable (see Adapt OER).

- Determine the logistics of using the OER within the lesson. For example, you may need to print handouts for learners. In other cases special software may be needed.

- Devise a method of evaluation or whether the currently planned evaluation needs adjustment (see Evaluation for more details).

What do these steps mean to you and your context? What additional step would you include? Blog on!

Because I am verbose and think too much (see all prior posts), I can’t hope to address all eight of these points, but they have helped me ponder a few things. These steps are for embedding an existing OER into a class or a course; in my case, I am creating an OER for a particular training I will deliver.

Cross-platform issues should be pretty easy to tackle–I’m using DokuWiki (here’s my first steps), and it is all text-based for ease of movement between devices. It renders perfectly when I access it on my Droid and, except for any videos I may include, the materials should be easy to download and print, if necessary, or store offline. I’ve just started learning and using this tool, so one thing I need to do is figure out whether there is an easy way to include, say, a button that allows a learner to save a particular file. I think the issue a learner would have, though, is that I try to fit the content onto one screen-sized “page” so there is not too much scrolling. That would mean more numerous but smaller files. I’ve seen wiki-based resources that do have a lot of scrolling, so I will need to figure out what my balance is between ease of reading on screen and ease of saving offline. I will have to investigate whether these DokuWiki text files could be “bundled” for download into subject groupings.

The target audience for this OER is very specific at the moment: I’ve been asked to create a writing curriculum for researchers who already have to write reports as part of their job, but reports that get disseminated to clients, partners, and the general public (in many cases). Their positions in this organization require the skills that they learned in graduate school (regarding data analysis and so forth) but also require them to communicate their findings to a wider audience than just their sociology professors. Newer associates, especially, have trouble with overuse of passive language and with burying the lead of their data “story.” They sometimes use phrases like “variables include student name…,” which mean very little to the public audience they are trying to reach. I have some mandates from the executive director that I must include, so there is an outside evaluator looking at these materials, too. Thus this OER is quite localized, which may or may not make it useful to a wider audience. However, the materials I want to incorporate may serve anyone who has to write public reports about what they do for a living.

I’m hoping that with the help of plug-ins in the DokuWiki software I may be able to incorporate some writing and revision interactive opportunities into the OER. That may or may not work, and I have a backup plan of Google Docs just in case. But I think what would be interesting is that learner engagement and interaction both inside and outside the system. I am thinking that we will do some writing in the workshops that may be incorporated into the wiki. Likewise, I will encourage them to go to the wiki and add/update/question things—that’s the beauty of wikis, after all.

In this project, there’s a tricky balance between a detailed academic approach (that is, in your writing, you need to be quite accurate about the data you are reporting) and a marketing/public relations/journalism approach (meaning that you want to make your prose accessible because you are hoping to enlighten/inform your audience about a situation in the community, for example). That means that in assessing materials to aggregate, I will have to pay attention not only to the quality of other materials I find but also to their approach and tone. A “how to” paper for an aggressive marketing campaign is not appropriate to include in my OER, for instance. These folks aren’t writing to sell anything; they’re writing to increase the knowledge of the community. Thus a few resources may be journalism sources, too.

March 5, 2012 2 Comments

One thing I thought about here: making sure you have "alternate text" for the image is helpful for a wide range of people with impaired vision.

In my prior day job working for a small K–12 textbook publisher, I was fortunate to glimpse a little bit of the localization process with printed materials for which the company was trying to gain an international market. At a meeting with the sales staff for the east and southeast Asian region, who traveled very long distances to illuminate us about their market, I learned to look at our materials a little differently. It was quite an experience.

In just one example, the textbooks they wished to offer in their schools contained pictures of boys and girls, age-matched to the level of the program, with a precisely calculated range of diversity (meaning, racial and gender proportions in the United States—all textbook publishers have very precise ways to log and count this). We sat down in a conference room to go over the program. One of the sales representatives looked at every single girl’s photo to determine whether any skirts were too short; we asked whether those photos of girls in pants were okay, and she thought that generally the schools that would use our materials would be okay with that. We would not likely gain entry anyway into schools with strict religious affiliation (within that region, Islam). We asked whether the U.S. diversity of race in these images would be acceptable, and she thought it would. In the end, we changed only one image in one book to better fit within the boundaries of that market.

That experience was brought to my mind when I was reading about making open educational resources more accessible and global. The issue of accessibility to me is not really a question: if you want to reach as many people as you can, pay attention to whether they can access what you have to say in different ways: through text-to-speech applications, for instance, or through the ability to magnify your text easily. However, trying to be too “universal” in your approach often ends up being vague; the best writing (and teaching) comes from the depth of detail. From a writer’s perspective, you want to clearly define your audience, your reader/user, and address particularly their possible context and needs.

When I searched for “globalization” and “localization,” I found a variety of marketing-related agencies, conferences, and information about localizing one’s content (translating, too). Small agencies seem to be springing up to help countries penetrate a market that’s foreign to them. This isn’t a new impulse. Certainly McDonald’s in India has a different set of menu items than does McDonald’s in Lancaster, Ohio. I looked at past conference programs for the Localization World conferences and saw a lot of process-based sessions (e.g., so different departments of your company aren’t translating and retranslating the same materials), adding translated metadata, “best practices” in the field, crowdsourcing across the globe, international domain names introduction, localizing legal agreements, translation management systems (TMSs), and so on. Clearly there is an ongoing conversation in the for-profit world.

When I searched for “globalization” and “localization,” I found a variety of marketing-related agencies, conferences, and information about localizing one’s content (translating, too). Small agencies seem to be springing up to help countries penetrate a market that’s foreign to them. This isn’t a new impulse. Certainly McDonald’s in India has a different set of menu items than does McDonald’s in Lancaster, Ohio. I looked at past conference programs for the Localization World conferences and saw a lot of process-based sessions (e.g., so different departments of your company aren’t translating and retranslating the same materials), adding translated metadata, “best practices” in the field, crowdsourcing across the globe, international domain names introduction, localizing legal agreements, translation management systems (TMSs), and so on. Clearly there is an ongoing conversation in the for-profit world.

But when I added “OER” to my search, because these seem to me by definition not-for-profit, I found that last year was the “1st International Symposium on Open Educational Resources: Issues for Globalization and Localization” held at Utah State University. (The conference proceedings may be found here.) The editorial opening the proceedings asks

How can we prevent neo-colonization and one-way flow of content based on the massive amount of content published by richer nations? How do we promote worldview and exchange if we do not build systems and capacity so that minority groups effectively contribute? (p. 4)

In my last post I talked about why students using Wikipedia is potentially a good thing that teaches them intellectual skills they need to discern a text’s point of view, etc. A similar logic applies here. It seems to me that the localization and globalization aspect of OER reuse isn’t up to me if I’ve created some resource for my own particular audience. That seems to be up to the colleague who wishes to use it in her context; that’s part of her reimagining what I’ve done. Having said that, however, the question of who in the world actually has the ability (economic, leisure, education, access to tools and electricity) to contribute OERs is a good one. The term “exchange” means more like back-and-forth, so perhaps the question of globalization and localization comes down, like most things, to economics and who owns the means of production.

February 24, 2012 8 Comments

Your source for official open educational resources

Your source for official open educational resourcesWikipedia, an encyclopedia that people can change to make accurate or more up-to-date, is also available online. It is a useful reference, but should never be used as a single source and should not be cited. However, there are footnotes and links that go with the articles that can be helpful in tracking down scholarly information on the topic you are researching.

I’ve been curious about the undertones of this short cautionary note. Clearly the words are mostly positive: people change Wikipedia entries to make them “accurate” and “more up-to-date.” Wikipedia is “useful” and “helpful,” too. Its footnotes and links direct you to “scholarly information.” However, Wikipedia should “not be cited” and “never be used as a single source.” Like many so-called scholarly resources, Wikipedia is peer reviewed. Literally, sometimes, thousands of people have agreed that the information contained about Thing X is accurate. That’s way more people than a scholarly journal relies upon when it vets articles for inclusion (perhaps three outside volunteer reviewers, with luck). What “scholarship” has that Wikipedia does not is an institutionalized history, external forces propping it up (think “publish or perish”), and sometimes a profit motive behind it (think of those conferences). Scholarly journals are officially sanctioned because…well, because we all sanction them.

My professor in my University of Manitoba “Open Educational Resources” course wondered whether the future of OERs would include “official” OERs. By that, I am assuming he means given the old okey-dokey by teachers, scholars, researchers, practitioners…or perhaps there will arise some sort of Council of Officially Blessed Resources for the Academy (COBRA)? More acronyms and bureaucracy always lead to order and civil society. With officialism we can sleep more soundly knowing that an organization is looking out for us. The squirrelier part of me wants to add “COBRA” to the Wikipedia page that lists all possible cobras as acronyms or snakes. I could perform an experiment to see how long it might take someone to stumble across the page and question the entry. To foment the illusion, I could also create a fake COBRA website complete with downloadable forms that ask respondents to “submit your Educational Resource with the accompanying 12-page form” and wait six weeks for “a decision from the committee of scholars in your subject area.” Using the web, I could insert photos of people in suits hovering over the round tables that hotels use when you tell them your meeting is “interactive.” Then I could get on Twitter and complain that COBRA rejected my educational resource, directing people to my anti-COBRA Facebook page where my friends would log in and demand that COBRA identify its rationale for acceptance of some OERs and not others.

With all this evidence, would anyone know it’s a mirage?

Last semester when I taught first-year composition, my students were surprised that I encouraged them to use Wikipedia; evidently, none of their other professors found it acceptable. But as I explained to them, using Wikipedia actually requires a little bit more of them as researchers and readers than does an article they find in a scholarly journal. They must actively verify whether the information on Wikipedia is worthwhile. How they accomplish that intellectual task is another opportunity to further their education and develop the skills they need to be actively engaged, questioning beings.

I suspect there may be some COBRA-type organizations springing up now or later, but it’s all rather silly. The only good reason I can think of for a body to sanction OERs is as a result of collectively organizing against those whose interest is vested in deminishing any online information source (say, for instance, textbook publishers) or those who want only their own version of what “education” means (say, Bill Gates, the Khan Academy, and so on). But a reactive position is never a strong one. The stronger position invites more and more people to create, redefine, criticize, question, and use OERs.

February 19, 2012 4 Comments

I always just love trying out new tools online. The ones listed in our course readings this week are familiar to me, although as I mentioned in my response to Vince J’s post (which, for some reason, didn’t save but won’t let me add a “duplicate” comment), they may be a little dated because of the readings dated 2008. Most of the tools that are listed seem to be downloadable software rather than cloud-based tools (aside from the hosted blogs, of course). As Damien mentions in his post, the Google Apps suite seems to be given shorter attention than it might deserve. Although I currently don’t work at an “institution,” I can see the value of this suite for education and business.

Google Calendar is one app I really like a lot and use incessantly for project-based work as a freelancer—I set up dedicated calendars for big projects, another calendar for ongoing editing work from my smaller clients, one for family, and one for my husband’s business to keep track of our events as well as post them on our website (www.DandyDogOhio.com). Reading Damien’s post led me to think more about how some of these tools are not necessarily geared toward OERs but could be useful. For instance, Google calendar would be a very basic learning management system: each week’s activities and readings can be set up as events; because of the seamless way it works with Gmail and Docs, it seems ripe for this.

I was surprised that the Aviary suite of online image and sound editing tools wasn’t among the ones listed as video tools in our readings this week. These are great substitutes for Photoshop, Illustrator, Audacity, and other tools. When I worked in an organization that did not have the Adobe tools, I was still able to manipulate photos and illustrations to make nice document. Also, one tool I really like that is not open source but is free is Microsoft Movie Maker; it comes with Windows installations. However, the newest version is not the best, so I downgraded back to an earlier version that had better functionality.

I used Movie Maker to create my final project for the Connectivism course last year that combined still photos, music, film clips, and animation. The animation was created by another online free source I like called GoAnimate. In fact, my husband and I use it so much we started paying a small fee each month to ease our creation of animations (see the Dandy Dog videos for our “commercials”). For video conversion, I really like Zamzar. My husband goes between Macs at school and our PCs at home, so this online service is extremely helpful for .mov to Quicktime conversions, especially. However, sometimes it takes awhile to convert if you use the free version, xo don’t try it under a deadline. RealPlayer‘s converter that comes with its free player has a version that will do some basic things like convert movie files so you can play them on a smartphone.

There are so many tools it is hard to quanitify them, and harder still for me to fault our readings for not including them as potentially useful for OERs. Two word-cloud creation programs I like are free, online, and easy to use: Wordle and Tagxedo. Both will do similar constructions, though I started with Tagxedo and still use it more than I do Wordle. Interesting textual analysis can happen with these tools; I could see an instructor loading a public domain book and having students use the resulting word cloud to make some statements about the text itself. I could see, also, using it in a composition classroom to help students see some of their composing “tics.”

Of course, Prezi is my all-time favorite online tool to create content. Prezi is so much more than a PowerPoint substitute, and it’s what I may end up using for our final project in this course. Prezi allows you to embed and link content, organizing it visually in a way that might be helpful to subjects that lend themselves to chunks of topics rather than linear steps. It is another tool that is basically free to use, but you can also pay a small fee to be able to download a desktop version.

Most of the tools I have been introduced to have been through the wonderful blog Free Technology 4 Teachers and the site for the Centre for Learning & Performance Technologies (which has reviews and information about open source, free, and commercial software). The tools I have used have mostly been tools that somehow are already familiar—like the Aviary tools, which make sense to me because they mimic the basic features of the Adobe tools I already know. There are other tools I think are interesting, but I never have a need to use them (not to mention, having time to learn them).

February 11, 2012 3 Comments

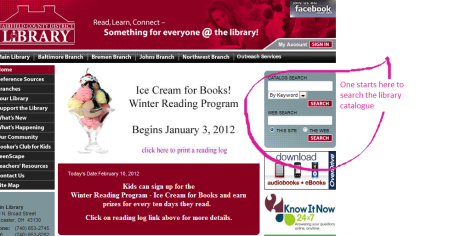

The closest libary to me is the Fairfield County District Library, a public library with one main location and four outlying branches. It is not intended as an academic library per se but as a community library.

The closest libary to me is the Fairfield County District Library, a public library with one main location and four outlying branches. It is not intended as an academic library per se but as a community library.

As a result of Gov. John Kasich’s drastic measures (shifting the burden of most public expenditures to the local level so he can say he has cut state spending), the local libary has substantially cut services, even closing at different times to furlough its employees. The Main branch is in Lancaster, Ohio, which is a small city of about 38,000, according to the latest Census data. Only roughly 13% of people here have their bachelor’s degree (0.3% have a doctorate; I guess that would be me and 10 other people). The median household income is just over USD$38,000, compared to the state’s median of USD$50,000. Poverty is estimated at about 10%. Luckily, it’s fairly cheap to live here.

Because I’m self-employed, I spend a lot of time at the library, and I see three general types of patrons during a typical workday: mothers with small children, elderly persons, and people using the computers. It’s unclear what the unemployment rate is here, but Ohio’s is about 10.5%, and my best guess is that Lancaster, given the educational levels of residents, may be higher than that.

People in Lancaster need their public library. And the library does a lot more than just check books in and out: it’s part of the larger community, and I’ve seen librarians take an hour helping someone with the online GED materials, for instance. Compared to university systems, a public library is ultra democratic. With the university library, you’re already putting a “firewall” between potential users and the library’s resources: the only way to really access materials is to be a student, faculty member, or staff. Public libraries, on the other hand, only ask that at some point you wander down and fill out a short form to get a card. They ask that you live there, but even that is negotiable. And around here, that card is good for your whole life.

So the Fairfield County Public Library is a repository for mostly physical and some digital materials. Of its limited digital materials, some are housed in collections (mostly photographs) and a few are linked to other sites that might be considered OERs. In the catalogue search, I typed in the keyword “writing” and got 2,943 hits. Narrowing my search to Electronic Resources culled the list down to 507 entries. I further narrowed it by the category Adult Education; the result was a list of 83 resources; here is the top of the list, which contains a link to an online course for high school students:

To go further I had to log in to the statewide Ohio Public Library Information Network, so in this way the Fairfield County library functions as a limited referatory. Here it gets a little more interesting. When I get to the OPLIN, it seems to share more of the qualities of a repository like the ones housed inside an educational institution; clicking the tab Skill Building for Adults gives me the following screen of choices, for example:

This is actually new to me: I have never before visited this site (which brings up a point for me, so what might that mean about other folks using the Fairfield County library, who may not be able to navigate as intuitively?), which contains learning objects called eBooks, Tests, and Courses. As the Educause article notes, many other respositories such as MIT organize their collections in these familiar ways (p. 5). You can search for a word and a type of resource. Many of the Test resources seem to be preparation for civil service positions, police officer exams, GED preparation, or practice for the Federal Clerical exam (these are the ones under adult skills). Just for fun I took the Diagnostic Writing Skills test; it turns out I’m pretty good at grammar and mechanics.

I chose a public library instead of one associated with a teaching institution because I think there is a huge “repository” potential in truly public libraries to collect helpful learning materials and make them available to all sorts of patrons. I did not expect that it existed in even a sort of limited form as it does in OPLIN. But that seems to be a first step in some basic OERs. Could a next step be for those currently placing OERs in more institutional settings to migrate some of them to public libraries? What kinds of audiences are some of the OERs that are online now (MIT, Open University, etc.) targeting and getting? It seems to me that public libraries could capture more types of people than just the university crowd. I don’t think the folks at my local branch are going to go online to find courses at MIT; I’m not sure that would even occur to them. But they might just start with a search at their familiar, comfortable library that will end taking them into learning experiences they may not have anticipated. And then who knows what could happen with their journey?

February 4, 2012 7 Comments

It’s impossible to disagree with the principle of, as Ilkka Tuomi says in Open Educational Resources: What they are and why do they matter, “a world where teachers and learners have free access to high-quality educational resources, independent of their location. Who wouldn’t want that? And what makes sense to me in the Cape Town declaration is the idea that if the public is paying for educational resources, the public should have free access, and “the public” includes the students using them. Last semester I taught some freshman composition courses, and my students at the community college paid more than $150 for the books for the course! For a writing course! The initiative from Cable Green and Washington State makes good sense for that reason alone. At the same time, however, that initiative is funded by a private foundation, Gates, which of course has its own agenda for educational change and certainly won’t keep underwriting this kind of development for every state in the union. In addition, it’s finding some challenges in the process (see thet commentary in the linked article about Washington State).

I want to be selfish for a minute, though, and figure out what all that means for me, given all the hats I wear. For instance, one of my larger clients is an academic journal publisher, for whom I edit papers appearing in seven different journals. I copyedit for the researchers and statisticians, making stylistic choices to adhere to the journal’s formal tone as well as ensuring things like all the citations in the text have sources listed in the References list. I also see journals, whether open or not, that are not edited in this way, and my eye immediately goes to the typos and infelicitous uses of language, errors, and usage problems. Likewise, when practitioners promote their theories on their blogs in order to foment that public discussion, I’m intrigued and interested in the results—while at the same time, I cringe at the run-on sentences, comma splices, typos, poor organization, unclear references, incorrect use of words like “comprise,” and so on. (I also cringe at these in the materials generated by my stepdaughters’ teachers.)

Definitely, my eye is more finely tuned than a normal person’s to grammatical nuances. But language primarily communicates, and poor language usage means that a reader is not receiving the clear communication she wants. Frankly, not all academics or teachers are, in fact, writers. Is there a place in open educational resources for qualified professional editing? Or do I need a new job?

This question becomes even larger: not everyone who knows about a subject is an expert in organizing content so that learners have the best experience they can, especially younger learners. Not everyone understands children’s cognitive and social-emotional development. That’s why K-12 teachers are required to attend hours and hours of professional training every year in order to remain a teacher and renew their licenses: in theory, at least, it helps them keep up with research in these subjects. That’s also why textbook publishers often pay for their editors to attend graduate school for MA degrees in education. My other clients are mostly educational publishers who are worried about the death of publishing. Sure, textbooks are expensive. Too expensive. But not everyone understands the enormous work that goes into creating them. Just as one example, at the K-12 level in the United States, each state has its own set of learning standards for, say, social studies. Maybe “history” in the generic sense doesn’t change…but what each state deems important makes it change, at least for the publishing industry. My old day job used to be keeping up with these developments in state legislatures and education departments, and publishers scramble to keep recreating textbooks when states change their minds about whether Thomas Jefferson is a crucial part of the U.S. History curriculum or not.

Perhaps it’s just that I don’t understand the economics of open source. How can I create “content” to share freely with the world when I need to be paid, somehow, in order to keep the electricity on?

One of the three strategies of the Cape Town Declaration includes the call for “educators, authors, publishers and institutions to release their resources openly. These open educational resources should be freely shared through open licences which facilitate use, revision, translation, improvement and sharing by anyone.” Fulfilling this and other strategies “will make it possible to redirect funds from expensive textbooks towards better learning.” I’m not seeing the step-by-step, flowchart kind of logic that shows this kind of business model, and I hope that my next course in the University of Manitoba Emerging Technologies in Learning certificate program, Open Educational Resources, gives me some ideas about how this can actually work in the context of U.S. elementary, secondary, and postsecondary education. The principles of open access to information and knowledge appeal to me greatly, especially as someone who simply loves to learn; I look forward to learning about some practical examples that show how it can work.

November 12, 2011 1 Comment

It’s ironic, really. Enrolled in the Emerging Technologies in Learning certificate program, participating (or trying to) in MOOCs, teaching myself skills in WordPress and other tools…I certainly appear to be on top of all things ed-techie.

It’s ironic, really. Enrolled in the Emerging Technologies in Learning certificate program, participating (or trying to) in MOOCs, teaching myself skills in WordPress and other tools…I certainly appear to be on top of all things ed-techie.

So when I started teaching again this fall as an adjunct instructor in English, hired about one week before classes began, I thought of the opportunities to work with students that technology gives us that I did not have 15 years ago, the last time I taught freshman composition courses. Would I have them each keep a blog? A class wiki? How could we do email and online conferences? Handed the books I was required to use and the essay rubrics I had to teach to, I was informed that the school also used Blackboard to communicate with students.

Wow, my first experience with a traditional learning management system! After all the LMS-bashing I’ve heard from my compatriots in MOOCs and read online, I looked forward to contributing a bash or two.

But between putting in the enormous amount of time dealing with the required texts and rubrics, the sheer volume of written work, and managing a full-time business on top of it…figuring out Blackboard hasn’t taken priority. As an adjunct, I am paid only for the hours I’m actually in the classroom—three per class—which works out to about $7 an hour when I account for the class preparation and grading and student meetings outside of class and supplementing the standard texts with materials that will actually help students write their required research papers. I simply can’t afford more time, which would be deducting from the time I spend writing and editing—what actually keeps me financially afloat. Forcing myself to limit the hours I spend on this teaching hobby sets up a choice between learning Blackboard or spending time with a student struggling with an essay. Of course the real-live person in need is going to win.

Considering that there are about eight full-time faculty and about 80 adjunct instructors in English, is it any wonder that the syllabus and texts I was given to work with look suspiciously like the ones I had 15 years ago? My students say they have not been using Blackboard because none of their instructors do, and I suspect that other departments have the same skewed faculty lineup. For an open enrollment community college, which has an equal mix of students planning to transfer for a four-year degree and students planning to earn their HVAC or culinary certificate, that skew is not surprising. This college is the only affordable option, and to keep it affordable means relying on part-time instructors who don’t get paid very much.

As I think more about it, the debates about doing away with traditional textbooks (my students claim that their rhetoric/grammar cost $78! $78?) could have an unintended consequence for adjunct faculty. If I had to find my own resources, gather them in the LMS, etc., how much more of my time would part-time teaching take up? And then how much more time to be innovative by crafting blog-based assignments and class wikis? I’m frustrated with forced choice I had to make, so frustrated that I’m not going back. (Yes, I know; in theory, the planning/supplementing time would decrease next semester because I’ve already got materials in place and my syllabus planned out…but I’m just not that type of teacher. I’ve always got to remake things so they have a chance to work better.)

We just had a big union fight here in Ohio (and our side won!) so that (full-time) public employees have the right to bargain collectively for their working conditions and benefits. I’m lucky I can walk away from part-time teaching because I have a good income in other ways; some of the adjuncts who are just out of grad school aren’t so blessed (I remember those days). I keep thinking about the loss to students, though, of teachers who have time not only to figure out Blackboard or any LMS but also go beyond that to engage students with new ways of communicating that are authentic and have the potential of a readership wider than just their freshman comp classroom and instructor. I’m jealous and sad I don’t get to be one of those teachers.